ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease) uniquely attacks both upper and lower motor neurons, unlike most neurodegenerative conditions that target specific brain regions. You’ll experience progressive muscle weakness while typically maintaining cognitive function—a stark contrast to Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. The disease advances rapidly, usually within 3-5 years, and requires distinctive multidisciplinary care coordination. Understanding these differences helps explain why ALS demands such specialized treatment approaches.

Key Takeaways

- ALS uniquely affects both upper and lower motor neurons simultaneously, while most neurodegenerative diseases target specific neural systems.

- Approximately 90% of ALS patients maintain cognitive function throughout disease progression, unlike Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease.

- ALS typically progresses rapidly within 3-5 years of diagnosis, faster than many other neurodegenerative conditions.

- Diagnosis relies on clinical examination rather than specific biomarkers, requiring evidence of both motor neuron types being affected.

- Treatment focuses on coordinated multidisciplinary care through specialized ALS clinics, addressing rapidly changing symptom management needs.

The Unique Pathophysiology of ALS: A Dual Attack on Motor Neurons

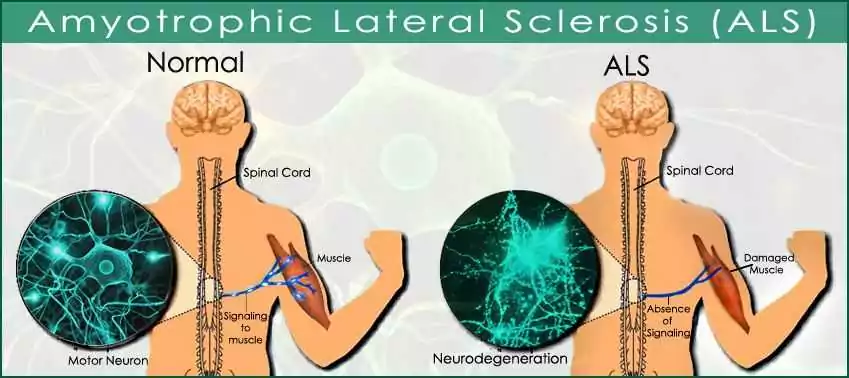

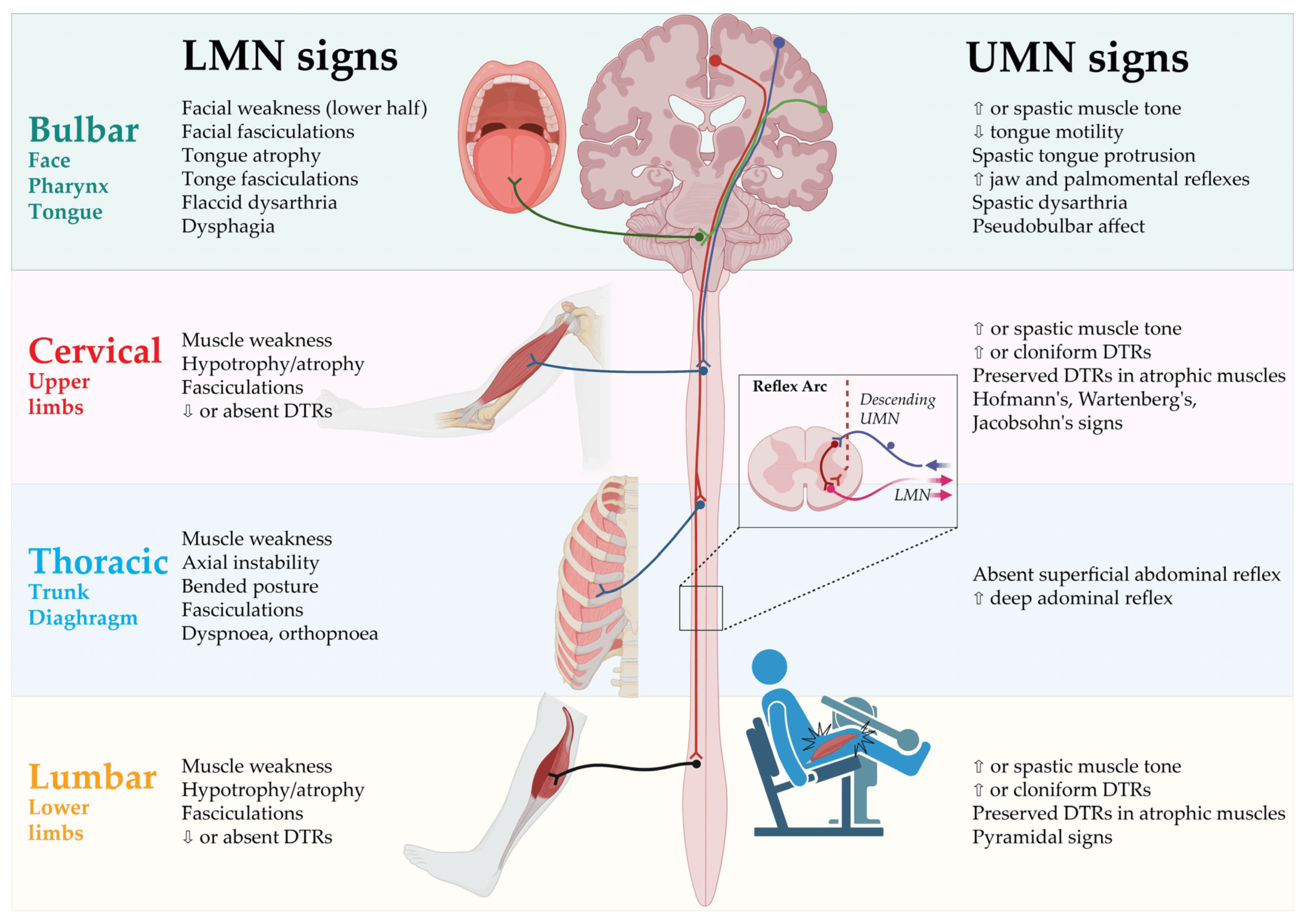

While many neurodegenerative diseases target specific brain regions, ALS stands apart with its devastating dual assault on both upper and lower motor neurons. This dual pathophysiology creates ALS’s characteristic combination of spasticity and weakness – a signature pattern that distinguishes it from conditions like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s.

When you examine ALS at the cellular level, you’ll find motor neuron degeneration occurring simultaneously in your brain’s motor cortex (upper neurons) and in your brainstem and spinal cord (lower neurons). This extensive attack disrupts the entire motor pathway, from initial movement commands to their execution in muscles.

Unlike diseases that progress through predictable anatomical patterns, ALS can begin focally but quickly spreads through contiguous regions, creating a cascade of failing motor systems throughout your body.

Symptom Progression: Why ALS Advances Differently Than Other Conditions

Unlike most neurodegenerative diseases that progress over decades, ALS typically advances relentlessly within 3-5 years of diagnosis.

What makes ALS particularly devastating is its predictable but rapid rate progression, with respiratory failure often being the final outcome.

While Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s may evolve over 10-20 years, ALS moves quickly through distinct stages, though symptom variability exists.

Unlike its neurodegenerative cousins, ALS rapidly progresses through defined phases, though individual symptom presentation may vary considerably.

You might notice some patients experience “limb onset” with weakness in arms or legs, while others develop “bulbar onset” affecting speech and swallowing first.

The progression pattern also differs from other conditions.

Rather than the fluctuating course seen in multiple sclerosis or the plateau periods common in Parkinson’s, ALS typically shows steady decline.

This relentless trajectory creates unique challenges for treatment planning and end-of-life care decisions.

Cognitive Preservation Amid Physical Decline: The ALS Paradox

While ALS devastates your body’s motor functions, your cognitive abilities often remain remarkably intact, creating what neurologists call the “locked-in” paradox.

Your preserved intellectual capacity amid progressive physical paralysis differs considerably from conditions like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, where cognitive decline frequently accompanies physical symptoms.

This cognitive resilience stems from ALS primarily targeting motor neurons rather than brain regions responsible for memory, reasoning, and consciousness, though researchers continue investigating the protective mechanisms that shield these mental faculties.

Intact Mind, Failing Body

One of the most striking paradoxes of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) lies in its selective assault on the body while typically sparing cognitive function.

Unlike Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, which often impair memory and thinking, ALS patients generally maintain their intellectual abilities even as physical deterioration advances.

You’ll notice this unique characteristic when interacting with ALS patients—they remain aware of their surroundings and capable of complex thought despite increasing immobility.

This preservation of mind amid bodily decline creates particular psychological challenges, as patients maintain full awareness of their changing capabilities.

This cognitive clarity allows many ALS patients to communicate their experiences and participate in treatment decisions throughout their journey, though it also means they’re acutely conscious of their condition’s progression.

Cognitive Resilience Mechanisms

The preservation of cognitive function in ALS represents a neurological paradox that continues to intrigue researchers and clinicians alike. While your motor neurons deteriorate, your brain’s cognitive centers often maintain remarkable flexibility. This selective preservation offers unique insights into neuroprotective strategies that might benefit patients with other neurodegenerative conditions.

| Cognitive Function | ALS | Other Neurodegenerative Diseases |

| Memory | Often preserved | Commonly impaired |

| Executive function | Usually intact | Frequently diminished |

| Language skills | Maintained in most cases | Often deteriorates |

| Problem-solving | Typically preserved | Generally declines |

| Emotional recognition | Mostly intact | Usually compromised |

You’ll find that approximately 90% of ALS patients maintain cognitive abilities throughout their disease course. Understanding these mechanisms may reveal new treatment approaches that leverage your brain’s natural protective capabilities.

Diagnostic Challenges That Set ALS Apart From Similar Disorders

Diagnosing ALS presents unique challenges that clinicians don’t encounter with other neurodegenerative disorders. Unlike Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, which have specific biomarkers or imaging findings, ALS diagnosis relies primarily on clinical examination and elimination of mimicking conditions.

The diagnostic criteria for ALS require evidence of both upper and lower motor neuron degeneration across multiple body regions, along with progressive spread of symptoms. This creates considerable symptom overlap with numerous conditions including multiple sclerosis, cervical myelopathy, and multifocal motor neuropathy.

You’ll find that misdiagnosis happens in about 10-15% of cases, with patients often seeing an average of three physicians over a 12-month period before receiving an accurate diagnosis.

This delay can greatly impact treatment initiation and clinical trial eligibility.

Treatment Approaches: How ALS Management Differs From Other Neurodegenerative Diseases

Unlike Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, ALS treatment focuses primarily on symptom management rather than altering disease progression.

You’ll work with a multidisciplinary care team that includes neurologists, respiratory therapists, physical therapists, and nutritionists who coordinate your care.

This team-based approach differs from other neurodegenerative conditions by emphasizing quality of life improvements through specialized interventions tailored to your changing symptoms.

Symptom-Based Treatment Approach

While most neurodegenerative diseases have some disease-modifying therapies available, ALS management primarily focuses on symptom relief and quality of life improvements. Your healthcare team will develop personalized therapies addressing your specific symptoms as they emerge.

| Symptom | ALS Approach | Other Conditions |

| Mobility | Adaptive equipment, PT | Disease-modifying drugs |

| Breathing | NIV, diaphragm pacing | Rarely a primary focus |

| Speech | Communication devices | Cognitive therapies |

Unlike Parkinson’s or MS where medications may slow progression, ALS symptom management targets functionality preservation. You’ll work with specialists including neurologists, respiratory therapists, speech pathologists, and physical therapists who coordinate care as symptoms evolve. This multidisciplinary approach differs greatly from other neurodegenerative conditions where treatment often centers around a primary medication regimen with supportive care as secondary.

Multidisciplinary Care Teams

The hallmark of effective ALS management lies in its extensive multidisciplinary care approach, which stands in stark contrast to treatment models for other neurodegenerative conditions.

While Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s often involve several specialists, ALS requires synchronized integration of neurologists, pulmonologists, physical therapists, speech pathologists, nutritionists, and mental health professionals working simultaneously from diagnosis onward.

This intensive care coordination addresses the rapid progression unique to ALS. Your team dynamics will evolve as symptoms advance, with respiratory specialists becoming increasingly central compared to the psychiatry-focused teams common in dementia care.

You’ll notice ALS clinics specifically designed for same-day consultations with all specialists, minimizing travel burden as mobility declines—a model rarely seen in other conditions where appointments typically spread across weeks or months at different locations.

The Genetic Component: Comparing ALS Hereditary Patterns to Related Conditions

Genetic mutations serve as critical pieces in the complex puzzle of neurodegenerative diseases, with ALS showing distinct hereditary patterns compared to Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s disease. While only 5-10% of ALS cases are familial (inherited), understanding these genetic variations helps researchers develop targeted therapies.

| Disease | Primary Genes Involved | Inheritance Pattern |

| ALS | SOD1, C9ORF72, FUS | Mostly sporadic; 5-10% familial |

| Alzheimer’s | APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, APOE | Complex; early-onset often familial |

| Huntington’s | HTT gene | Autosomal dominant (100% penetrance) |

You’ll notice ALS’s familial patterns differ greatly from Huntington’s disease, which is always inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, meaning a child with an affected parent has a 50% chance of inheriting the condition.

Conclusion

Imagine your nervous system as a high-functioning city. In Alzheimer’s, the memory library gradually crumbles. In Parkinson’s, the traffic signals fail. But with ALS, you’re watching the delivery system collapse while the city’s planning department remains intact. You’ll face a unique journey that requires different maps than other neurological travelers. Your path isn’t easier or harder—just distinctly your own, demanding specialized support and understanding.